Fruits  Seed Development

Seed Development

SEED DEVELPOMENT

The development of the fruit from flower starts from the stage of fertilization and continues which is described as below:

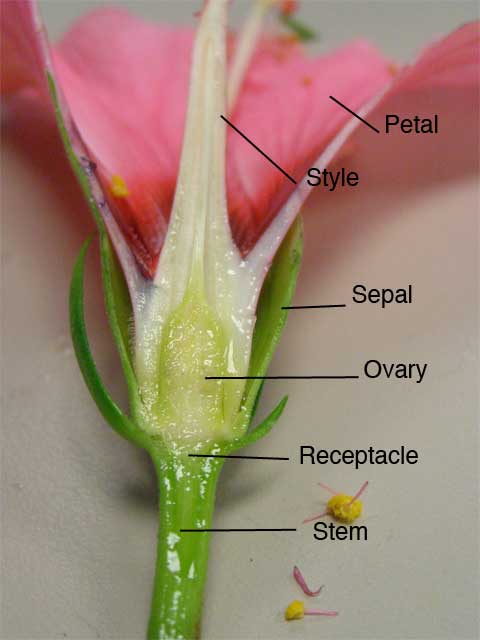

Flowers are the true reproductive organs of flowering plants. The "male" part is the stamen or androecium, which produces pollen (male gametes) in anthers. The "female" organ is the carpel or gynoecium, which contains of egg (female gamete) and is site of the fertilization. While the majority of flowers are perfect and hermaphrodite (having both male and female parts in the same flower structure), flowering plants have developed numerous morphological and also physiological mechanisms actually to reduce or prevent self-fertilization. Heteromorphic flowers have short carpals and long stamens, or other wise vice versa, so animal pollinators cannot easily transfer pollen to the pistil (receptive part of the carpel). Homomorphic flowers could employ a biochemical (physiological) mechanism called self-incompatibility to discriminate between self and non-self pollen grains. In other species, the male and female parts are morphologically separated, developing on different flowers.

The main growth of the fruits from the seeds include three main parts which includes:

Fertilization

Embroyology

Fruits and Seeds

Fertilization

During period of the fertilization the embryo-sac lies in a close proximity to the opening of micro Pyle, into which the pollen-tube has penetrated, the separating cell-wall becomes absorbed, and the male or sperm-cells are ejected into the embryo-sac. Guided by the synergetic one male-cell passes into the oosphere with which it fuses, the two nuclei uniting, while the other fuses with the definitive nucleus, or, as it is also called, the endosperm nucleus. This is remarkable double fertilization as it has been known, although only recently discovered, has been proved to take part place in widely-separated families, and both in Monocotyledons and of a prothallium after a cause following the reinvigorating union of the polar nuclei. This view is still maintained by those who are differentiate two acts of fertilization within the embryo-sac, and regard that of egg by the first male-cell, as the true or generative fertilization, and that of polar nuclei by the second male gamete as a vegetative fertilization which gives a stimulus to development in correlation with the other.

If, on the other hand, the endosperm is the product of an act of fertilization as definite as that giving rise to the embryo itself, we have to recognize that twin-plants are produced within the embryo-sac—one, the embryo, which becomes the angiosperm us plant, the other, the endosperm, a short-lived, undifferentiated nurse to assist in the nutrition of the former, even as the subsidiary embryos in a pluri-embryonic Gymnosperm may facilitate the nutrition of the dominant one. If this is so, and the endosperm like the embryo is normally the product of a sexual act, hybridization will give a hybrid endosperm as it does a hybrid embryo, and herein (it is suggested) we may have the explanation of the phenomenon of xenia observed in the mixed endosperms of hybrid races of maize and other plants, regarding which it has only been possible hitherto to assert that they were indications of the extension of the influence of the pollen beyond the egg and its product. This would not, however, explain the formation of fruits intermediate in size and colour between those of crossed parents. The signification of the coalescence of the polar nuclei is not explained by these new facts, but it is noteworthy that the second male-cell is said to unite sometimes with the apical polar nucleus, the sister of the egg, before the union of this with the basal polar one.

Embroyology

The result of fertilization is the development of the ovule into the seed. By the segmentation of the fertilized egg, now invested by cell-membrane, the embryo-plant arises. A varying number of transverse segment-walls transform it into a pro-embryo—a cellular row of which the cell nearest the micropyle becomes attached to the apex of the embryo-sac, and thus fixes the position of the developing embryo, while the terminal cell is projected into its cavity. In Dicotyledons the shoot of the embryo is wholly derived from the terminal cell of the pro-embryo, from the next cell the root arises, and the remaining ones form the suspensor. In many Monocotyledons the terminal cell forms the cotyledonary portion alone of the shoot of the embryo, its axial part and the root being derived from the adjacent cell; the cotyledon is thus a terminal structure and the apex of the primary stem a lateral one—a condition in marked contrast with that of the Dicotyledons. In some Monocotyledons, however, the cotyledon is not really terminal. The primary root of the embryo in all Angiosperms points towards the micropyle. The developing embryo at the end of the suspensor grows out to a varying extent into the forming endosperm, from which by surface absorption it derives good material for growth; at the same time the suspensor plays a direct part as a carrier of nutrition, and may even develop, where perhaps no endosperm is formed, special absorptive "suspensor roots" which invest the developing embryo, or pass out into the body and coats of the ovule, or even into the placenta.

The formation of endosperm starts, as has been stated, from the endosperm nucleus. Its segmentation always begins before that of the egg, and thus there is timely preparation for the nursing of the young embryo. If in its extension to contain the new formations within it the embryo-sac remains narrow, endosperm formation proceeds upon the lines of a cell-division, but in wide embryo-sacs the endosperm is first of all formed as a layer of naked cells around the wall of the sac, and only gradually acquires a pluricellular character, forming a tissue filling the sac. The function of the endosperm is primarily that of nourishing the embryo, and its basal position in the embryo-sac places it favourably for the absorption of food material entering the ovule. Its duration varies with the precocity of the embryo.

Some deviations from the usual course of development may be noted. Parthenogenesis, or the development of an embryo from an egg-cell without the latter having been fertilized, has been described in species of Thalictrum, Antennaria and Alchemilla. Polyembryony is generally associated with the development of cells other than the egg-cell. Thus in Erythronium and Limnocharis the fertilized egg may form a mass of tissue on which several embryos are produced. Isolated cases show that any of the cells within the embryo-sac may exceptionally form an embryo, e.g. the synergidae in species of Mimosa, Iris and Allium, and in the last-mentioned the antipodal cells also. In Coelebogyne (Euphorbiaceae) and in Funkia (Liliaceae) polyembryony results from an adventitious production of embryos from the cells of the nucellus around the top of the embryo-sac. In a species of Allium, embryos have been found developing in the same individual from the egg-cell, synergids, antipodal cells and cells of the nucellus. In two Malayan species of Balanophora, the embryo is developed from a cell of the endosperm, which is formed from the upper polar nucleus only, the egg apparatus becoming disorganized.

The picturization of the fruit from flower of tomato is explained below

Fruits And Seeds

As the development of embryo and endosperm proceeds within the embryo-sac, its wall enlarges and commonly absorbs the substance of the nucellus (which is likewise enlarging) to near its outer limit, and combines with it and the integument to form the seed-coat; or the whole nucellus and even the integument may be absorbed. In some plants the nucellus is not thus absorbed, but itself becomes a seat of deposit of reserve-food constituting the perisperm which may coexist with endosperm, as in the water-lily order, or may alone form a food-reserve for the embryo, as in Canna. Endospermic food-reserve has evident advantages over perispermic, and the latter is comparatively rarely found and only in non-progressive series. Seeds in which endosperm or perisperm or both exist are commonly called albuminous or endospermic, those in which neither is found are termed exalbuminous or exendospermic. These terms, extensively used by systematists, only refer, however, to the grosser features of the seed, and indicate the more or less evident occurrence of a food-reserve; many so-called exalbuminous seeds show to microscopic examination a distinct endosperm which may have other than a nutritive function. The presence or absence of endosperm, its relative amount when present, and the position of the embryo within it, are valuable characters for the distinction of orders and groups of orders. Meanwhile the ovary wall has

developed to form the fruit or pericarp, the structure of which is closely associated with the manner of distribution of the seed. Frequently the influence of fertilization is felt beyond the ovary, and other parts of the flower take part in the formation of the fruit, as the floral receptacle in the apple, strawberry and others. The character of the seed-coat bears a definite relation to that of the fruit. Their function is the twofold one of protecting the embryo and of aiding in dissemination; they may also directly promote germination. If the fruit is a dehiscent one and the seed is therefore soon exposed, the seed-coat has to provide for the protection of the embryo and may also have to secure dissemination. On the other hand, indehiscent fruits discharge these functions for the embryo, and the seed-coat is only slightly developed.

With multi-seeded fruits, multiple grains of pollen are necessary for syngamy with each ovule. The process is easy to visualize if one looks at maize silk, which is the female flower of corn. Pollen from the tassel (the male flower) falls on the sticky external portion of the silk, then pollen tubes grow down the silk to the attached ovule. The dried silk remains inside the husk of the ear as the seeds mature, so one can carefully remove the husk to show the floral structures. The seed development of the flesh of the fruit is proportional to the percentage of fertilized ovules.